(Running time 31:34)

–

Jay McLean, Part I

In 1915, Jay McLean was a second-year medical student who wanted to become a surgeon.

But McLean didn’t want to be just any surgeon. He wanted to be a Johns Hopkins trained surgeon. But Johns Hopkins was the department of William Halstead and Hugh Young and Harvey Cushing. Only the best and brightest got a chance to train there.

To prove his worth, McLean sought out a research mentor – and met William Howell, an eminent MD-PhD pathologist who had previously served as the dean of the medical school.

Howell tasked McLean with examining various tissues for pro-coagulant substances. And after completing a number of experiments involving pulverized pig brain and ground ox heart and oxalated dog plasma, McLean found some.

But McLean also found something else – a substance that inhibited the coagulation of blood.

(McLean J. Circulation, 1959; 19(1); 75.)

The substance McLean identified is what we now call heparin. It’s one of the most important drugs in all of medicine – and it was discovered by a medical student doing a research project.

This is not the only such important medical advance made by a medical student. In fact, medical students have made or at least contributed significantly to many major medical advances, from the discovery of insulin to the development of anesthesia and x-rays.

So I’ve got some good news for you:

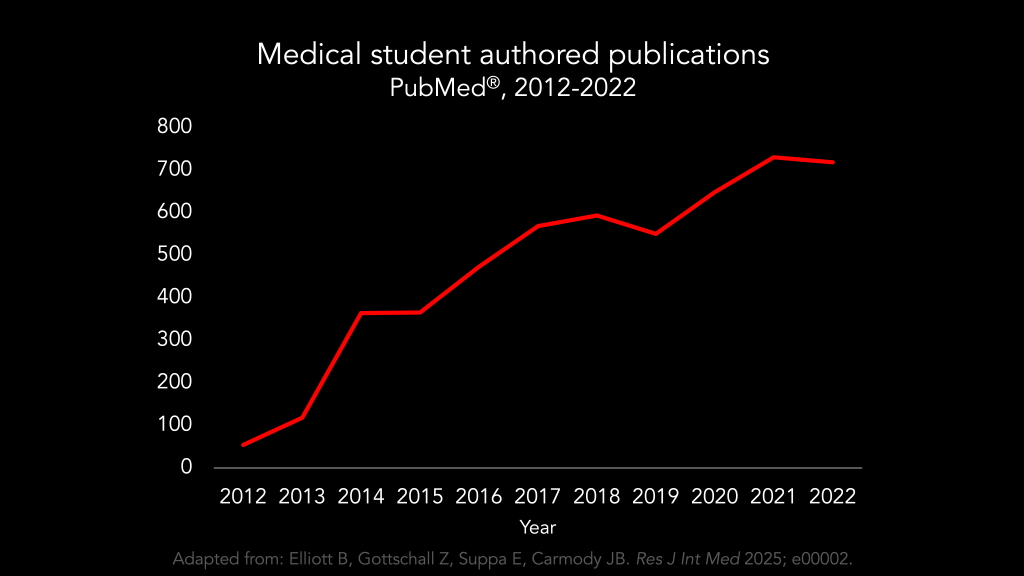

Medical students are doing more research than ever before.

Surely, we are entering a scientific rerenaissance, with medical students leading the way.

–

The Research Arms Race

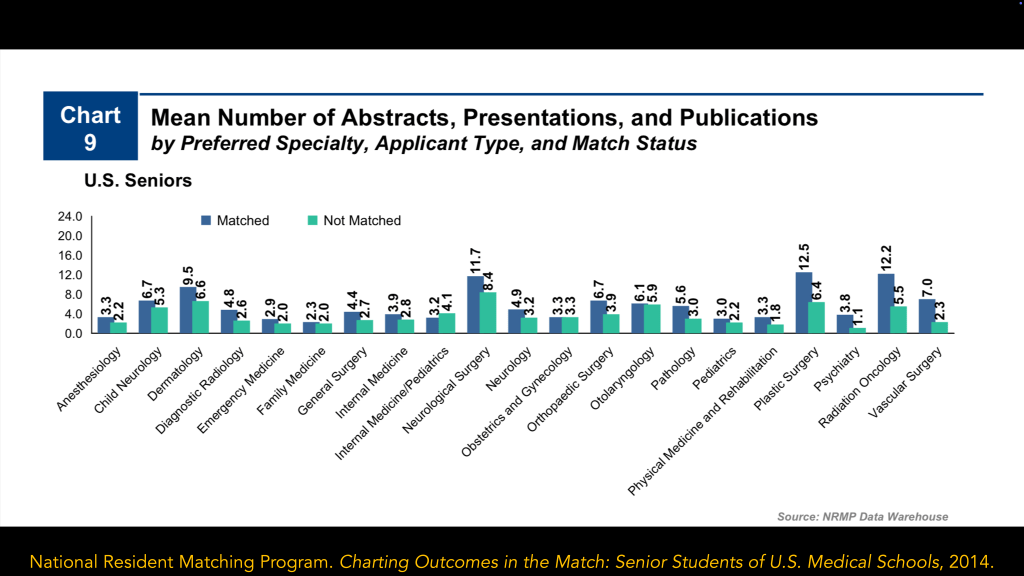

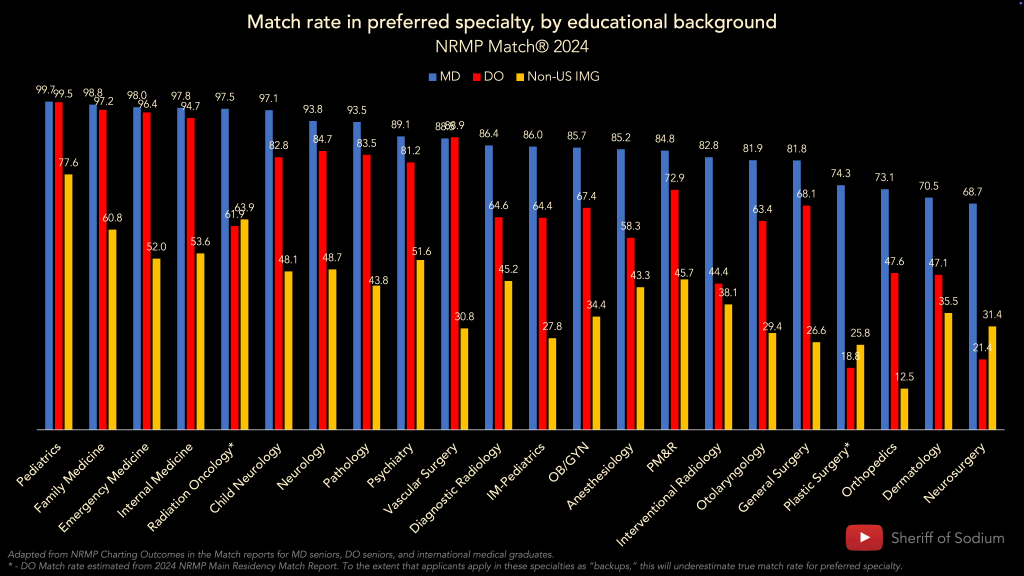

Lest ye doubt that this new golden era is upon us, please also inspect these data from the 2024 National Resident Matching Program’s Charting Outcomes in the Match report for MD seniors.

The future is bright for our understanding of diseases of the skin, where the average successful dermatology applicant reported having 27.7 abstracts, presentations, and publications in 2024.

Note also at the scientific progress we are making in orthopedic surgery, where the average applicant had 23.8.

But where we really see the boundaries of knowledge being pushed beyond the wildest dreams of our predecessors is in specialties like plastic surgery and neurosurgery, where in 2024, the average applicant had 34.7 and 37.4 research items that they had contributed to our collective understanding by the time they submitted their residency applications.

This is scientific progress so unbounded that it can’t even be contained by the NRMP’s y-axis, which only goes up to 24. The towering peaks on the graphic above are already truncated just to make them fit.

And if you’re not yet utterly gobsmacked by this explosion in science, then please consider how much applicants’ research output increased in just the past 10 years.

(Data from 2014 Charting Outcomes in the Match report.)

The increase in research output is so remarkable, in fact, that in most specialties, the average successfully-matched applicant in 2014 has less research output than the average unmatched applicant in 2024.

Never before have we seen such a wellspring of interest in scientific research than we are seeing today. There’s a study in every student, just waiting to get out! Surely, this unprecedented desire to contribute to the body of scientific knowledge will lead to discoveries even greater than Jay McLean’s. Right? Right???

–

Thing is, I don’t think this explosion in academic output has anything to do with advancing science. It’s just the latest battleground in the Residency Selection Arms Race.

Somewhere along the way, doing research became less about answering questions and instead turned into an extra credit assignment for the most driven students who are eager for any opportunity to seize a competitive advantage. Completing a research project is yet another checkbox that applicants must tick off, right between a high USMLE Step 2 CK score and leadership in the dermatology interest club. What they’re discovering is less important than whether it’s PubMed indexed. And I think it’s a shame.

–

I’ve been talking about this for several years. And when I do, I frequently get pushback from those who believe that all this increase in research is good, actually.

After all…

- Medicine is fundamentally a scientific endeavor – so shouldn’t we want all doctors to do research?

- Without an incentive to participate in research, many medical students won’t – but some that try it will like it and become productive investigators.

- By doing research, doctors could learn skills about critically interpreting research that may improve their practice in the future.

I’ve addressed many of these objections elsewhere – so here, let me take on more of a steelman version of the “pro- research in residency selection” argument.

–

There will always be competition in residency selection. The only choice we have is how we want applicants to compete.

If applicants compete with USMLE scores, or by getting honors on their clerkships, some good for society could come out of it. But let’s be honest: while a few more points on Step 2 CK or an extra clerkship honors may well be the difference between an applicant becoming an orthopedic surgeon or not, those things don’t really have the potential to change the world.

But encouraging scientific research might. Because every now and then, you could get a Jay McLean.

–

If we concede that are potential benefits to having more medical students do research, then the question becomes: is the cost worth it? And there are many costs to consider.

–

The first is opportunity cost.

Medical school lasts 4 years – same as it did back when Jay McLean was in medical school, when there was less medicine to learn. Same as it did when I was in medical school, which wasn’t that long ago, but significantly fewer students did research, and those that did completed fewer projects.

What’s getting squeezed to make room for students to do all these projects? And is that going to make them more or less effective physicians in the future?

(Of course, thanks to the research arms race, for a growing number of students, medical school doesn’t just last 4 years: more and more students are adding an extra year to their undergraduate medical education to focus exclusively on research. So we should also consider the costs of progressively lengthening medical training.)

–

We should think also about costs to fairness. Research opportunities are not distributed equally among medical schools, and there is little reason to presume that the distribution that exists mirrors the distribution of talent or potential to become an effective neurosurgeon or dermatologist. There are disparities in medical student research output that mirror those related to other opportunities in medicine and society at large. Should that bother us?

–

There are financial costs, too. The actual cost of doing these projects is very difficult to quantify – but likely enormous. But for many students, just publishing their research incurs significant costs. As of 2022, around 15% of medical student research articles were published in journals with mandatory submission or publication costs. (That figure is up from around 3-4% in 2012.)

–

There’s at least one other important cost to consider – and that’s the cost to the integrity of research itself.

Despite the growing quantity of medical student publications, there’s little suggestion that the quality of those publications is increasing. There’s been no increase in high-quality study designs, for instance – and around a quarter of all medical student authored publications receive a grand total of zero citations. Undoubtedly, there are many papers with meritorious science – but there are also lots of surveys with low response rates, case series from a single department, least publishable unit offshoots of a mentor’s project, p-hacked associations from EMR data mining, and opportunistic perspectives with “COVID-19” in the title. Medical students are publishing more papers, sure – but Jay McLean dropping a beaker of anticoagulated cat blood on his mentor’s desk, it ain’t.

The reason for this preference for quantity-over-quality are obvious.

When many residency programs receive >100 applications for every position they’re trying to fill, it’s a simple matter for program directors to discern, at a glance, who has done more research. It’s much harder – if not entirely time-prohibited – to judge who has done meaningful research.

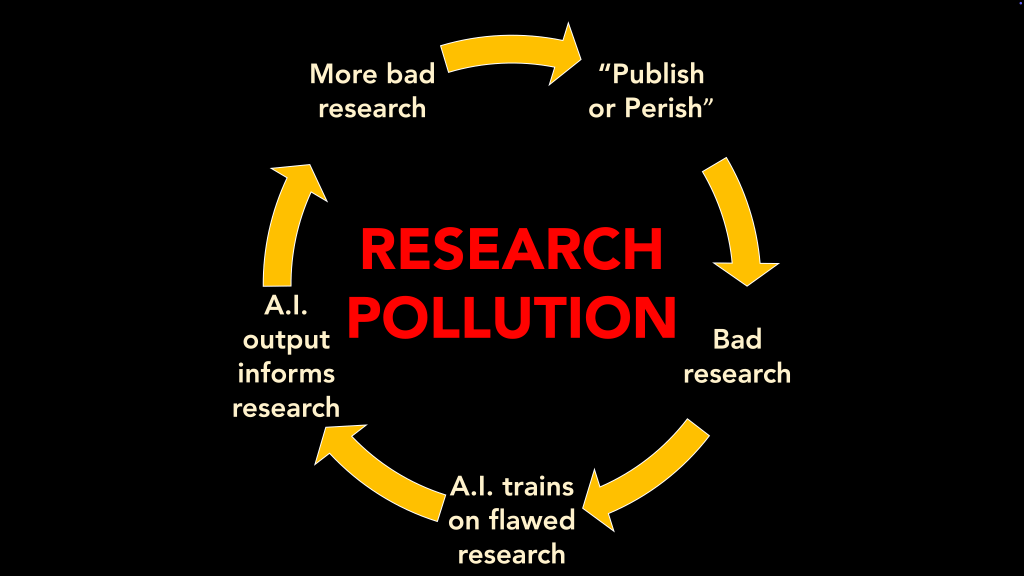

But focusing on the number of publications incentivizes other threats to research integrity, too.

A substantial number of publications listed on residency applications are “ghost publications” that can’t later be found in the literature. While many of these are simply abandoned projects that have served their purpose as an application adornment, some may be altogether fraudulent. In one recent meta-analysis of orthopedic surgery applicants, 20% misrepresented their publication record (by switching author order, changing journal names, claiming authorship of a nonexistent article, etc.).

When we turn research into a game applicants have to win in or to get into residency, we shouldn’t be surprised when some applicants bend the rules. Or break them outright. Because even when an applicant’s name appears on a publication – a real publication, not a ghost publication or misrepresented publication – it’s no guarantee they actually did the work or wrote the paper.

(for the low, low price of just $1800).

There’s a bustling black market for authorship, where prospective authors can add their name to papers on most any subject.

(But before you get your wallet, caveat emptor. Are these good papers? Well, maybe not. They might just have been written by a chatbot. And they might only be publishable in a specific pay-to-play online journal… which also might be owned and operated by the same person who prompted the bot to write the paper.)

–

Medical research has the potential to do good things for society. The fact that more medical students and residents are doing it has the potential to be an engine to drive forward that good. But only if things are framed in a certain way.

This reframing would require significant, systemic change – but there are a few simple, readily-implementable changes that we can pursue in the meantime.

–

Cap research items in ERAS and ResidencyCAS

If we want applicants pursue quality over quantity, we can’t give them a platform that showcases the longest list of publications. Limit research items to 3-5 – and let each applicant show you their best work.

I’ve argued for this before. And I’ve heard the pushback.

I appreciate that some residents would prefer to compete with number of publications, and believe that the number of publications they’ve generated tells programs something meaningful about themselves. They’re right about that – but that doesn’t mean that we should all suffer the externalities of incentivizing research pollution on scale.

I further appreciate that some applicants, such as those with MD-PhDs, have earnestly generated research output that can’t be captured in a snapshot like this. But program directors screening applications don’t have all day. The more papers all applicants list, the less anyone’s list gets looked at. And remember, we have an interview for a reason.

Capping research items may have unintended consequences, but it shifts the incentives away from sheer volume and toward higher quality. On balance, that’s what we need.

–

Add full-text links to all listed research items

In a world where computers exist and applications are created and reviewed on computers, there’s no reason to add friction between a research reference in the application and the actual work it corresponds to.

Make it easy for program directors and interviewers with similar interests to actually read applicant’s papers. Plus, clickable DOI link or uploaded PDF would also put a stop to some of the low-grade integrity issues mentioned above. You’d have to have a real pair to misrepresent your research to a program director when discovering the truth is only a mouse click away.

–

Improve data reporting for applicants’ research output

I love the NRMP’s Charting Outcomes data – but their reporting on research output has at least two major limitations.

First, the NRMP aggregates all research items (abstracts, presentations, and publications). This leads to a certain amount of double-counting, because the same project may turn into multiple abstracts and presentations before it is published. Disaggregating these figures would provide more informative data to applicants.

Second,

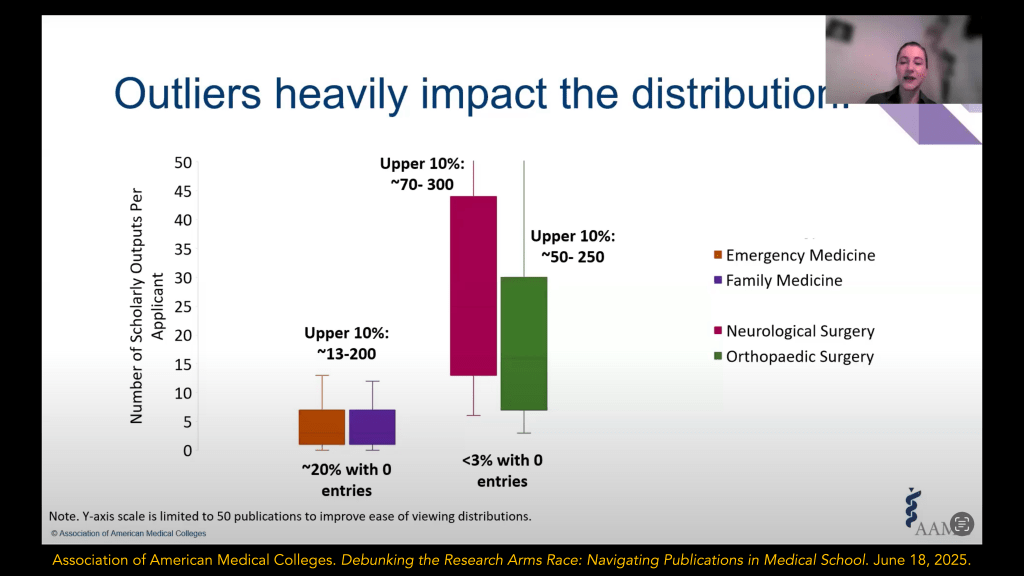

Second, the only data point reported by the NRMP is the mean. While the mean is a perfectly good measure of central tendency for normally-distributed data, the distribution of applicants’ research output is likely to be skewed.

(Screenshot from AAMC webinar.)

Outliers heavily influence the mean – which means that many applicants who are actually quite typical feel like they’re way behind their competition in research output. Higher quality data reporting from might help ensure that students’ perception of the research arms race actually matches the reality.

_

Mission-driven, transparent communication on selection criteria from programs

In residency selection, applicants’ behavior is driven by programs’ preferences – either real or perceived. When a program director says jump, applicants say how high.

So this research arms race is do programs actually want it?

Do programs believe that applicants who win in the research arms race are truly those who are best suited for training in orthopedics or neurosurgery or dermatology? If so, then we can all keep chilling. But if not, some different guidance about what programs really care about is in order.

–

Jay McLean, Part II

In case you were wondering, Dr. McLean got into the Johns Hopkins surgical program. (I’m sure the strong recommendation of his research mentor helped.)

But here’s what’s interesting.

McLean never published much after his groundbreaking 1916 paper. I could only find a couple of case reports – ironically, on the use of heparin to treat patients with gangrene and endocarditis. He held a few academic appointments but spent the latter part of his career as a private practice surgical oncologist in Georgia.

I think this reflects the great truth about research: most students aren’t interested in it. As soon as they don’t have to do it, they won’t. It’s a vehicle to get them to a place they actually want to go.

But that doesn’t mean it can’t be a good for society. It can. And sometimes, it is.

There’s more potential good in using research for residency selection than some other things we might use – but to maximize the good and minimize the harm, we have to structure the system appropriately. There have to be incentives to do good work instead of just CV stuffing. There must be impediments to dishonesty and fraud and the dissemination of AI-generated slop that functions as research pollution and benefits no one except the owners of pay-to-play journals. We have to give some serious consideration to leveling the playing field if this the competition we want applicants to play. And we have to have some honesty about opportunity costs and diminishing returns.

Jay McLean did good work. He got into the residency program of his dreams. And he left us with something that’s saved innumerable lives. It’s a win-win.

Obviously, it’s naïve to think that, in the modern era of bioscience when most of the low-hanging fruit has long since been harvested, that very many medical students could ever independently make discoveries of this magnitude. But I don’t think it’s naïve to think that we could transform our wasteful and harmful research arms race into something that could actually bring some good to the competitors and society at large.

–

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE:

Should all residents publish research?

The Residency Selection Arms Race, Part 3: The Research Arms Race