Last fall, authors from the National Board of Medical Examiners published a paper in Academic Medicine describing an association between physician USMLE performance and reduced in-hospital mortality and shorter length of stay.

I read it – then did my best to ignore it, in the hopes that others would do the same.

But after the paper came out in print, I witnessed enough self-aggrandizing non-critical discussion on social media that I finally said enough was enough. This paper needed a Sheriff of Sodium Journal Club.™️

Fair warning: my criticisms were so numerous that it took nearly 45 minutes to get through them all. If you’re pressed for time, lemme hit the high points, which range from “noteworthy, but not necessarily problematic” to “yeah, that’s a little concerning” to “the very foundation of this study is suspect.”

–

1. There’s financial conflict of interest

The authors are affiliated with the National Board of Medical Examiners. The study funding came from examinees’ USMLE registration fees.

Pointing out the existence of financial conflict of interest is not an allegation of research misconduct. The issue is implicit bias. Even in a simple project, researchers have substantial degrees of freedom in how to model relationships, measure exposures and outcomes, and adjust for confounders.

Now imagine we added a 30th team, composed of professional soccer referees. Where do you think their model would fall?

–

2. The study is inherently non-replicatable

No other group can replicate these results… because no one else has access to every physician’s USMLE scores. Would the results hold up if things were modeled even slightly differently? We’ll never know.

–

3. Some analytic decisions may be necessary but introduce selection bias

Patients who were transferred from one hospital to another were excluded. This is likely to lead to an unusual distribution of patients and illness severity at smaller hospitals (who can transfer patients who are likely to have poor outcomes) and larger hospitals (who can’t).

–

4. Other decisions weren’t explained at all…

How variables were chosen to be included in their multivariable models is unexplained. There are no unadjusted odds ratios to review, no forward or backward variable selection, no mention of previously-described associations between mortality and LOS and the included variables, etc. They just stuffed things in there.

–

5. …and others are really hard to justify

Although the paper focuses on hospital outcomes, the authors chose to exclude any physician who identified themselves as being a hospitalist. (This curious decision inspired an especially scathing rant.)

–

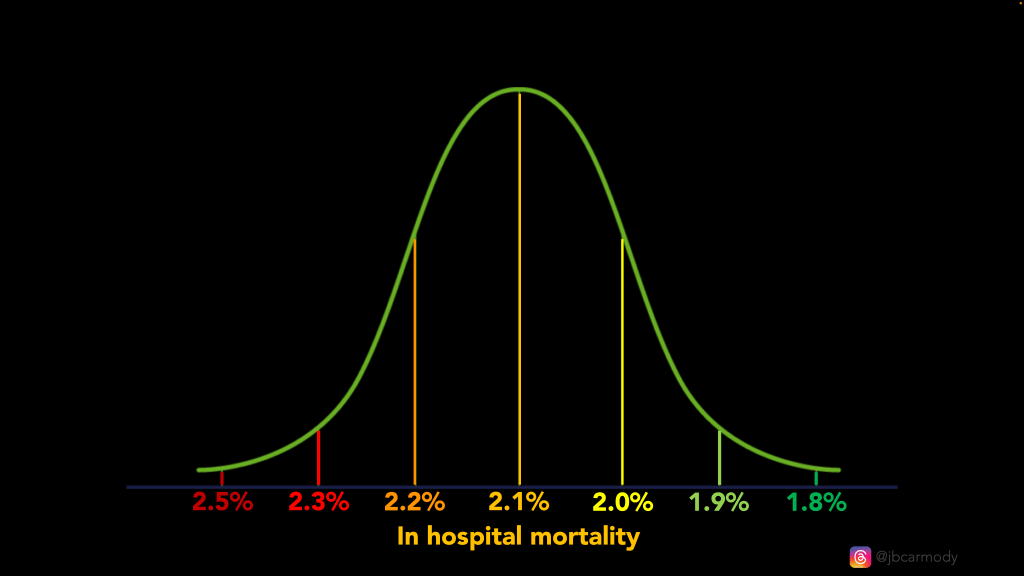

6. Even if you accept the modeling, the effect size is small

The authors compare the effect size of USMLE scores on patient mortality to that of low-dose aspirin for secondary prevention of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease.

I was less impressed. Even large differences in USMLE scores were associated with only small absolute differences in patient mortality (0.2% for two thirds of doctors).

The impact on length of stay was even smaller: a one standard deviation increase in USMLE composite score was associated with a reduction in length of stay of less than 2 hours.

“Why, thank you. You should see my composite USMLE score.”

–

7. Attributing a patient outcome to a single doctor is a fundamental problem

And here’s the biggie.

Medicine is a team sport. To accept these results, we have to believe that a patient’s outcome was entirely determined by their One Doctor, whose partners never covered call; who direct admitted the patient themselves so they wouldn’t have to go through the ED; who never consulted cardiology or neurology for their patients with an MI or stroke; and who didn’t lean on a radiologist to read their films or an ICU physician to try to prevent their patient from dying on the floor.

If you can’t reliably attribute an outcome to an individual physician, nothing else really matters.

–

8. The results still smack of residual confounding

If you want to reduce your risk of inpatient mortality and shorten your length of stay, a physician with high USMLE scores only gets you so far (OR 0.95 for mortality, 0.99 for LOS).

If you believe this modeling, what you really need is a female physician (OR for mortality 0.82, p<0.001) who trained in family medicine, not internal medicine (OR 1.05 for LOS, p=0.01) and is not board certified (OR 1.05 for LOS, p=0.01)

–

9. Any effect is likely mediated by the Matthew effect

We use USMLE scores in residency selection – so small differences in scores may set in motion bigger differences in Match outcomes, quality of training, job opportunities, etc. – which may be a better explanation for any differences in patient outcomes.

To the extent an effect exists, you could probably find the same result if, instead of USMLE scores, you considered medical school prestige. Or organic chemistry grades in college. Or even per capita income for a doctor’s birth ZIP code.

–

The bottom line:

This study was done for a noble purpose: to meet the InCUS recommendation “to accelerate research on the correlation of USMLE performance to measures of residency performance and clinical practice.” Given the priority residency programs place on high USMLE scores – and the extraordinary time and treasure spent by medical students to provide them – we need to know that the juice is worth the squeeze.

But I don’t think this study gets us there. Worse, the fact that it exists – and was published by an expert authors in a reputable journal – will serve as a deterrent from evaluating USMLE validity in the future.

You can imagine it now:

“USMLE scores are known to be associated with lower in-hospital mortality and shorter length of stay,” with an authoritative superscript linking to a paper that few will read beyond the abstract.

Sigh.

–

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE:

Match Day 2024: Winners & Losers Edition

ERAS and Financial Conflict of Interest at the AAMC