Introduction

The United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 is the first test in a four-part examination that serves as a prerequisite for state licensure for all allopathic medical school graduates in the United States. The minimum passing score is set by the USMLE Management Committee, and since the USMLE began in 1992, the minimum passing score has been adjusted upward six times.

Cynics have criticized this policy, noting that these increases to the passing score were made in the absence of any objective evidence that former standards failed to weed out incompetent practitioners. Others have noted that today’s physician workforce includes many doctors whose Step 1 scores would fail using contemporary standards. Yet these short-sighted objections may overlook an important role that a consistent policy of increasing the minimum passing score could play in increasing physician quality in the United States. Rather than “score creep,” we questioned whether the careful manipulation of the minimum passing score may in fact be a powerful engine for quality improvement.

Therefore, we sought determine whether the USMLE Management Committee’s policy of repeatedly increasing the minimum passing score would result in improvement in a universally-acknowledged measure of physician quality: the USMLE Step 1 score.

Methods

We reviewed public data from the USMLE program related to standards for and performance on the Step 1 examination from 1997 to 2017. The minimum passing score on the USMLE is determined by the USMLE Management Committee. Overall physician quality was measured by the national mean score on the USMLE Step 1 examination.

Descriptive statistics were calculated, and linear regression was performed to evaluate the relationships between continuous variables. The student’s t-test was used to compare means between normally-distributed groups. Statistical analyes were performed using IBM SPSS version 25 (Armonk, NY), with a two-sided p <0.05 was considered significant for all analyses.

Results

Between 1997 and 2017, the minimum passing score for the USMLE Step 1 was increased 5 times, for a total increase of 16 points (176 to 192; median 3 points/increase). Since the standard deviation for Step 1 is 20 points, this reflects a total increase of 0.8 SD.

The mean Step 1 score for U.S./Canadian medical students rose in parallel with the minimum passing score, from 212 in 1997 to 229 in 2017 (Figure 1). The increase in physician quality, as assessed by the national mean Step 1 score, fit a linear function, with each year corresponding to a 0.9 point increase in Step 1 score (95% CI for slope: 0.8-1.0; model R2 = 0.94).

Figure 1.

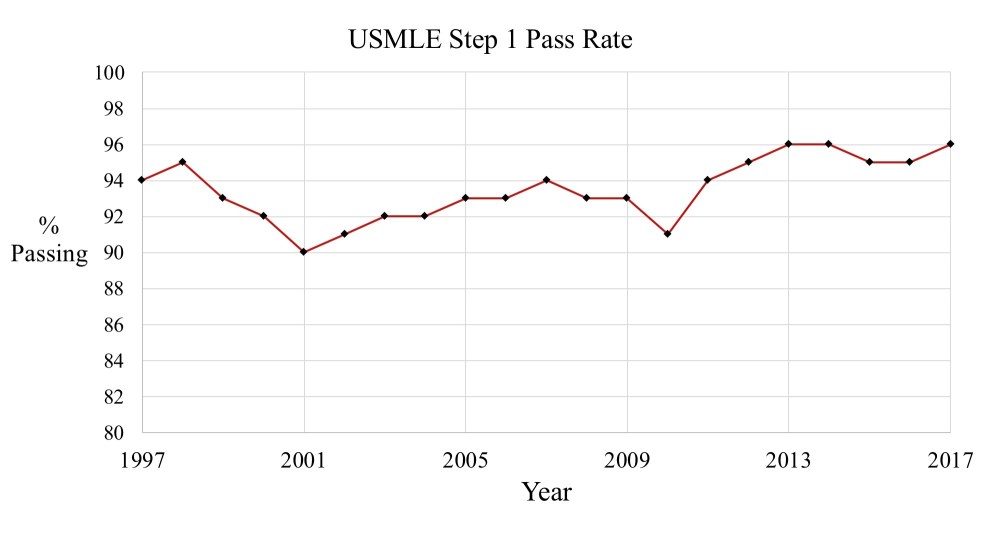

Despite the increase in the minimum passing score, the difference between the national mean and the minimum passing score remained remarkably consistent (mean 35.4 points for initial year of score increase vs. 36.1 points for non-increase years; p = 0.43). Similarly, the overall pass rate was relatively unchanged, varying from 90-96% throughout the period of interest (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Discussion

Here, we have shown that the calculated and carefully-executed policy of periodic increases to the USMLE Step 1 minimum passing score has resulted in substantial and sustained improvements in physician quality. At its inception in 1993, the minimum passing score for the USMLE Step 1 was 176, and the mean score was just 200. Today’s mean of 229 points reflects an improvement on the order of almost 1.5 standard deviations from the original test. In fact, over half of the USMLE’s original test-takers would fall in the bottom decile of performance had they achieved the same score in 2014-2017.

Even more remarkably, these important increases in the national mean score have been achieved without any decrease in the test’s first-time pass rate. Cynics may suggest that the Step 1 pass rate is being manipulated as a tactic to maintain the appearance of legitimacy for the test, since licensing exams with excessive pass rates may be criticized as offering little in the way of discriminatory value to regulatory bodies. Such detractors may deride “score creep” or point out the significant negative impacts to students who fails this mandatory licensing exam (including financial losses, a profound sense of personal failure, alterations to life/career course, and negative implications for the student’s institution). However, such adverse consequenses affect at most 4-10% of U.S./Canadian students, and even these must certainly be offset by the dramatic improvements in mean USMLE score achieved over the previous decades.

Indeed, though designed as a binary licensing exam, the validity of the Step 1 score as an unbiased marker of physician quality is implicitly understood, and other researchers have exhaustively catalogued the available evidence demonstrating that USMLE Step 1 score is a valid surrogate for physician quality, patient-oriented health outcomes, and measures of population health.

Beyond this, Step 1 scores play an invaluable role in residency selection. Recently, the presidents of the National Board of Medical Examiners and Federation of State Medical Boards authored an insightful defense of using Step 1 scores for residency selection, highlighting the test’s utility in counteracting racial bias, ensuring a level playing field for international and non-elite U.S. medical school graduates, and protecting patient safety by limiting medical students’ use of Netflix and Instagram.

Left unmentioned in their analysis, however, was the likely benefit of higher Step 1 scores on the residency match process. Currently, suboptimal USMLE Step 1 scores (and the important knowledge deficits they represent) may present a barrier to applicants seeking to match in the most competitive fields. Yet using the regression noted above, we predict that the mean score on USMLE Step 1 will increase to 250 by the year 2040 – a value on par with the mean USMLE Step 1 score for matched applicants in the most competitive fields (such as Dermatology, Orthopedics, Otolaryngology, and Plastic Surgery). Surely the future of these fields is bright, as previously-closed doors will soon spring open wide to accommodate a torrent of now-qualified applicants.

This study does have important limitations. For instance, it must be emphasized that many of the physicians on the USMLE Management Committee – the body responsible for setting the minimum passing standard – obtained licensure before the existence of the USMLE, or during early years when USMLE standards were substantially lower. It is therefore unknown whether these physician leaders successfully memorized all named skull foramina or Krebs cycle intermediates, or how such important knowledge deficits might impact their ability to optimize the minimum score setting policy. While our model above predicts a national mean of 270 by 2062 and a mean of 300 (a perfect score) by 2096, this model assumes stable linear growth in the national mean score. Yet it is entirely possible that modern graduates, endowed with 30 point higher scores on the Step 1, could achieve more rapid or even exponential growth in the national mean score, brining these lofty targets into reach even sooner.

Conclusions

While alternative conclusions are possible, we believe that these data demonstrate how a carefully-orchestrated policy of increasing the minimum passing score on the USMLE Step 1 has resulted in substantial gains in future physician quality. In light of the clear benefits of higher Step 1 scores to society as a whole, these findings represent a laudable achievement in testmaking policy and should serve as a model for other examinations.