In August 2019, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) withdrew the accreditation of the University of New Mexico’s neurosurgery program.

This, by itself, was noteworthy. Programs don’t lose accreditation very often: in 2019, the UNM program was one of only two neurosurgery programs to be so penalized. But there was another reason this story caught my attention.

See, there were eight neurosurgery residents who left the UNM program. And when they did, the university hired twenty-three advanced practice providers to replace them. In other words, it required 3 paid professionals to replace the clinical work that was previously accomplished by each of the residents. And since the average neurosurgery nurse practitioner earns around $115,000 a year – nearly twice as much as a resident – the loss of accreditation cost the university five times as much as they would have paid if they had kept their residents.

It’s an observation that begs a question: how much are resident physicians worth? Here, we’ll try to answer it.

The short answer

More than they’re paid, that’s for sure.

At the hospital where I work, wanna know the most dreaded time of the year to be on call? It’s not Christmas, or the first of July, or Friday the 13th. It’s the first weekend of November, when all our residents go away on retreat to a local resort.

If you’re the attending that weekend, you suddenly become responsible for every aspect of your patient’s care – not in a philosophical or medico-legal sense, but in a very gritty, minute-to-minute sense. You’re in the trenches writing H&Ps, processing discharges, fielding pages from nurses, and – especially – entering orders. Lots and lots of orders.

(And look, I don’t mean to trivialize resident work, much of which requires skill, judgment, and compassion. But yeah, there are a lot of orders.)

I’ve always believed the value of our resident retreat was twofold. In part, it provides valuable bonding time and much deserved R&R for the residents. But just as importantly, it provides a visceral reminder to the attendings of just how much work the residents do.

But how much is that work worth, in real dollars and cents?

The answer is, it’s complicated.

The balance sheet

In theory, estimating the value of a resident should be a simple matter of creating a balance sheet. You just total up all of the revenue brought in by residents, then subtract the cost of training them.

The cost of training a resident is pretty straightforward. You’ve got their salary and fringe benefits, and the salaries and benefits of the program leadership and support staff, as well as some miscellaneous program expenses. These figures vary from program to program, but they’re all figures that can be directly obtained or reliably estimated.

But the financial benefits of training a resident are quite opaque. So although the arithmetic is simple, getting reliable numbers to crunch isn’t.

Still, today we’re gonna take a shot at it. Fair warning: even though I’m going to provide only a brief overview, this will inevitably necessitate some trips into the weeds.

Patient care revenue

This is a surprisingly difficult figure to get at, in part because – with rare exceptions – resident physicians do not bill for their services.

Of course, their attendings do… and having residents usually allows attending physicians to bill more. The more time attending neurosurgeons spend on scut work, the less time they have to spend in the OR engaged in the gainful practice of neurosurgery. But give them a team of residents, and they can practice ‘at the top of their license’ by spending the maximum amount of time doing the most remunerative portions of the job.

How much value an individual resident adds is highly variable. If the ICU is already full, adding another internal medicine resident lightens the workload, but can’t result in any additional attending billing. In some circumstances, it’s possible that adding a resident may actually reduce attending billing. The average private practice dermatologist may see 50+ clinic patients a day, but it’s difficult to keep up that pace while precepting residents. Similar considerations apply to other outpatient-heavy specialties (like family medicine), as well as specialties like radiology and pathology.

Regardless, to the extent that a resident allows an attending to manage more patients or bill existing patients at a higher level of service, having a resident adds financial value.

–

Increased hospital services

Having residents doesn’t just increase attending billing – it also increases the hospital’s ability to bill for its services. A financially happy hospital is one where the ICUs are full, there’s rapid bed turnover in the ED and on the wards, and the lab and radiology departments are abuzz with the latest diagnostics. Residents are invaluable in keeping up that pace.

Moreover, having residents allows a hospital to care for higher-acuity patients. It’s difficult to provide, say, high-level oncology or cardiovascular care without having residents and fellows to share the intense clinical workload.

But having residents leads to other indirect financial benefits that are even harder to quantify. Many hospitals spend exorbitant sums on physician recruitment… but it’s easier to recruit a physician to a hospital with residents to help with on call duties. And since many new attendings take jobs at the institution where they did their residency, having a residency program can give the institution access to a steady stream of junior (i.e., lower paid) attendings without having to pay for third-party recruiters and expensive national searches. (This may be one reason that the for-profit HCA Healthcare system has become the single biggest sponsor of residency positions in the United States.)

Unfortunately, precise figures for all of the hospital benefits are elusive, because those benefits indirect and apparent only upon inspection of financial data for the system as a whole. It’s both easier and more strategic for hospitals to ignore these impacts of having residents, since doing so allows the use of selective accounting to claim that residency programs are actually money losers, administered only out of educational benevolence.

–

Governmental subsidies

Even though resident physicians increase revenue for attending physicians and their hospitals, having residents often enables an additional revenue stream: governmental subsidies.

This wasn’t always the case. In the old days, hospitals paid for resident training by building those costs into the bills they sent patients. But in 1965, Congress acknowledged resident medical training as a public good deserving of public investment, and firmly established federal funding for graduate medical education costs with the Medicare Act.

(What’s interesting is that Congress intended for the public funding to be temporary, with language in both the House and Senate reports noting that the funds were intended to last only “until the community undertakes to bear such educational costs in some other way.” Unsurprisingly, once governmental funds became available, hospitals have had little interest in undertaking how to bear these costs any other way.)

Nowadays, the Medicare subsidy for graduate medical education comes in two parts. The first is direct GME (DME), and as the name suggests, it’s intended to provide financial support for the direct costs of training residents – things like resident salaries, faculty teaching stipends, program administration, building maintenance, etc.

The exact amount a hospital receives for DME varies. It’s based on a regional per-resident amount (based on funding models from the 1980s, adjusted for inflation). In 2017, the average per resident amount was $102,875 for primary care residents and $100,956 for other residents. That figure then gets discounted based on the percentage of inpatient days for Medicare patients at the resident’s institution.

The other payment covers indirect GME expenses (IME), and is intended to compensate hospitals for the increased expenses of training residents. This was negotiated in 1983, based on the belief that residents order more expensive and unnecessary testing; that physicians engaged in teaching residents become more inefficient as a consequence; that hospitals that have residents are more likely to care for complex patients and need to invest in expensive technology; etc. Whether these arguments are always true is debatable, but what is clear is that IME funding has grown become the biggest piece of the residency funding pie for many programs. (If you want to see how much your hospital received, it’s listed on a downloadable .csv at the CMS website.)

IME payments are calculated based on a percent add on to each Medicare DRG payment that the hospital receives. How that add on is calculated gets complicated, and there are wide disparities in IME payments to hospitals. In fact, around 1/5 of teaching hospitals receive approximately 2/3 of all IME payments.

For instance, while inpatient-based residency programs that care for lots of Medicare beneficiaries (read: internal medicine) may receive generous IME subsidies, an obstetrics-heavy OB-GYN program may care for very few Medicare patients and qualify for very little. Such programs may see many patients with Medicaid – and though most states’ Medicaid programs provide some funding for GME, the amount is highly variable, ranging from essentially zero (West Virginia) to more than $1 billion a year (New York).

Similarly, with the exception of a handful of children with end-stage kidney disease, pediatric residents care for no Medicare beneficiaries and receive no IME payments. There’s a different federal program that provides subsidies to freestanding children’s hospitals, but only around half of pediatric residents train in such facilities.

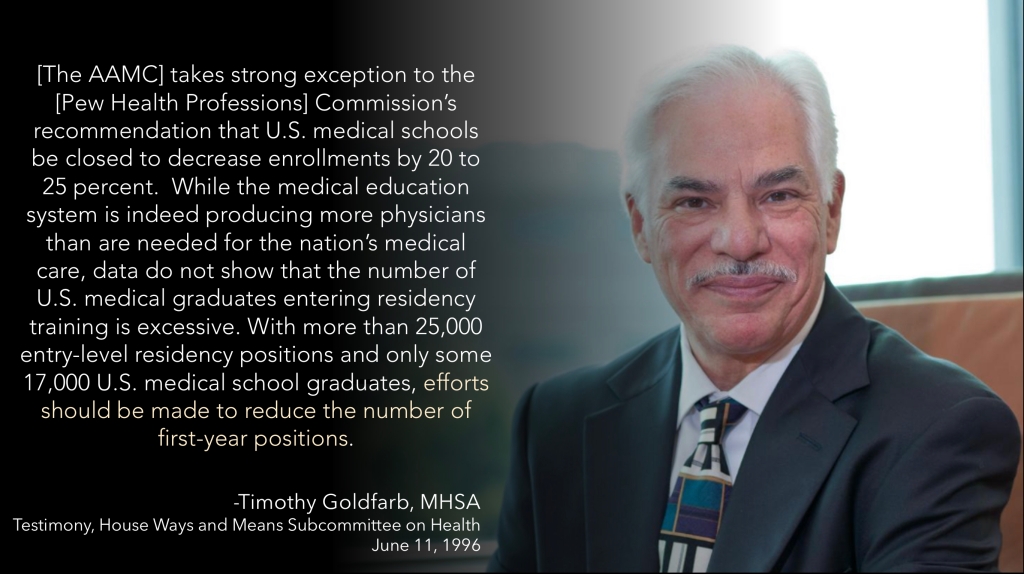

But if that isn’t complicated enough, not every residency position even qualifies for DME funding, either. As part of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, Congress capped the number of residents eligible for DME funding at 1996 levels. This occurred in the managed care era, amidst concerns that the country would soon be oversupplied with doctors. (The story behind the cap is an interesting one that may be deserving of its own post on the Sheriff of Sodium in the future.)

Capping DME payments did, in fact, constrain the growth of new GME positions… at least temporarily. In 1996, there were 20,563 PGY-1 positions available in the NRMP Match (a reasonable, though imperfect surrogate for the total number of GME positions available). But a decade later, the Match included only a little over a thousand more. Since then, though, there has been steady growth in the total number of GME positions available, with over 35,000 PGY-1 positions available in the 2021 NRMP Match.

(As an aside, the growth of new GME positions that are ineligible for the Medicare DME payments provides strong empirical evidence that this subsidy is not needed to make the average resident position profitable for hospitals.)

So how much are residents worth?

It should be clear by this point that, based on the number of variables involved and the difficulty (if not impossibility) of pinning them down with certainty, defining a resident’s financial value is a challenging task. Still, that hasn’t stopped some experts from trying.

In Elisabeth Rosenthal’s excellent book, An American Sickness, she notes:

The median cost to a hospital for each full-time resident in 2013 was $134,803. That includes a salary of between $50,000 and $80,000. Federal support translates into about $100,000 per resident per year. Researchers have calculated that the value of the work each resident performs annually is $232,726. Even without any subsidy, having residents is a better than break-even deal.

It’s not entirely clear what researchers Rosenthal is citing here, but the dollar figure is identical to the one reported in this paper, which estimates the value of unreimbursed procedures performed by surgical residents. It’s an eye-popping figure, sure, but one that hardly seems generalizable or comprehensive enough to inform broad debates.

The question of resident value over training costs was most authoritatively analyzed in 2013 by the RAND Corporation. In a 74-page analysis, the value of adding an additional internal medicine resident is bracketed between -$101,178 and $253,910, based on the availability of governmental subsidies and variability in training costs and changes in clinical revenue. (In comparison, adding an additional cardiology fellow resulted in a net financial impact ranging from -$107,589 to $340,199 per year.)

However, it strains credulity to believe that hospitals would choose to create a new residency position that would generate a net six-figure loss. So if we assume that the only residency positions that hospitals have chosen to create are ones they believed would be financial winners, then it’s probably reasonable to take the midpoint of the positive integers from the RAND estimate – $126,955 – as the best point estimate of a single resident’s financial impact. But even if you reject the premise that hospitals would only add profitable residency positions, if you accept the RAND figures as credible, then the financial impact of the average resident would still be $76,366 in the hospital’s favor.

(Of course, since the RAND analysis was based on 2010 figures, if we assume appreciation at the rate of inflation, we’d get point estimates of $93,804 or $162,322 depending on whether you believe hospitals know what’s in their best interest or not.)

So why don’t residents earn more?

If the average resident generates so much money for their employer, why aren’t they paid more? Hold that thought… because I’ll return to answer it soon in a different post.

–

ADDENDUM

Since this post went up two days ago, I’ve received a handful of e-mails and direct messages claiming that these figures are way off, and asserting that the average residency position barely breaks even – if that. One department chair compared having a residency program to having a yacht – a status symbol that requires substantial and ongoing financial inputs to keep it afloat. Another faculty member shared how her department had chosen to add two additional residents, but then their clinical revenues decreased – so now their chair wants the faculty to open a new Saturday clinic to generate more RVUs.

Look, it’s absolutely true that simply adding a resident doesn’t necessarily add financial value. If adding another resident allows the hospital to do more business, then yeah, the new resident has the potential to add value in excess of their training expenses. But if the hospital is already doing as much business as it can reasonably do in its specific market situation, then adding a resident won’t help it do any more.

And it’s certainly possible that some hospitals have chosen to create residency programs or positions that are, in fact, money losers. But I am deeply skeptical about claims of financial losses… at least if accounting is considered broadly.

What do I mean?

Well, one classic trick of hospital administration is to silo off pieces of the business, then insist that each of those silos keep their individual balance sheet in the black.

For instance, many hospitals lose money on their OB units. So if you’re an administrator, you can go to the obstetricians, show them all the red on their balance sheet, and say with a straight face how you couldn’t possibly justify devoting any more financial resources to their service line since it’s so unprofitable. Of course, this selective accounting ignores the fact that, without obstetrics, the hospital wouldn’t be able to fill its profitable neonatal intensive care unit. (Those dollars only show up on the pediatrics ledger.)

Similarly, an old friend of mine from medical school works as an emergency medicine physician in a major academic hospital. Every year, his department gets told how they need to work faster and smarter because the ED is losing so much money. Yet every couple of years, the hospital expands the ED capacity and staffing… which is certainly a curious thing to do for a service that’s purportedly hemorrhaging money.

If you look at the books, and consider the ED’s revenues and expenses in isolation, it may very well not pay for itself. But is that really fair accounting? Without the ED to feed the wards and the ICUs and the OR and the cath lab, your hospital is gonna leave a lot of money on the table. But by using budgetary gerrymandering to carefully silo off clinical departments, you can create a system in which the majority of the hospital’s services are claimed to be financial losers… when in reality, they’re loss leaders for an overall profitable enterprise.

I strongly suspect this same type of selective accounting applies to most assertions about residents having negative financial value. To see the true picture of a resident’s financial impact requires being able to see the institution’s complete financial picture, which is something that even department chairs don’t see. (It also requires an honest financial evaluation of the “no residents” counterfactual and the revenue losses and/or replacement costs that would be required.)

I said it before, but I’m gonna say it again: it simply beggars belief that those in a position to see the full balance sheets and do the calculus required would choose to create residency positions that are financial losers. Say what you want about hospital administrators, but they’re not dummies. They’re savvy businesspeople who know not to throw good money after bad – and how to pounce on a good deal when they see one.

–

ADDENDUM, PART 2: For anyone interested in watching or sharing a video of this post, there’s one available on the Sheriff of Sodium YouTube channel.

–

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE:

The Match, Part 5: The Lawsuit

Why Do We Have Residency Training?

The Residency Selection Arms Race, Part 1; On Genghis Khan, Racing Trophies, and USMLE Score Creep

Resident Unionization, Part 1: Lessons from Hamburger University