On August 19, 2020, the Otolaryngology Program Directors Organization (OPDO) announced an unprecedented change to the residency selection process.

Let’s review what happened – and then we’ll break it down, Winners & Losers style.

WHO

Otolaryngology residency applicants and programs.

WHAT

Preference signaling.

Applicants in otolaryngology this year will have the option of sending a signal of interest to up to 5 programs. Program directors can use these signals to identify applicants with strong interest in their program – and may choose to use this information when deciding whom to interview.

WHERE

Online.

The portal will be managed by administrators from the OPDO, the otolaryngology program directors professional association. Applicants will submit their list of preferred programs in September, and the OPDO will transmit the names of applicants to programs in time for application reviews in late October.

WHEN

Now, folks.

This will go live for the 2020-2021 application season.

WHY

Because gone are the days when simply submitting an application to a program could be viewed as a credible signal of interest in that program.

In 2019, applicants in otolaryngology submitted an average of 66 applications apiece. We’re in the era of Application Fever, and the temperature runs hotter each year.

Video on the rationale behind and inner workings of the #ENTSignaling system.

So who wins – and who loses – when otolaryngology goes live with preference signaling? Without further ado…

WINNERS & LOSERS

WINNER: Otolaryngology applicants.

Big applause here from me to the otolaryngology program directors for coming up with an applicant-friendly way of tempering the chaos caused by Application Fever. Unlike previous efforts – like requiring program specific essays – that impose extra costs on students, allowing applicants to send a signal of interest is an inexpensive, fair, and sensible way of trying to help interested candidates and programs find each other.

–

LOSER: Most other specialties.

Ever since COVID-19 caused the world to fall apart back in the spring, we’ve known that this year’s residency application season would be more challenging than any other.

In response, many specialties looked warily at the gathering storm clouds and chose to do… exactly nothing. Now, those program directors will reap their just rewards when they’re buried under a pile of indistinguishable applications this season.

–

LOSER: Pre-interview “love notes.”

The NRMP has always allowed applicants and programs to express interest in one another. Most of the “love notes” to program directors occur post-interview and include some carefully-phrased innuendo about how the applicant intends to rank that program very, very highly.

Expressing interest in a program pre-interview is fair game, too, though these expressions suffer from the same perceived lack of sincerity. I have a sneaking suspicion that the type of applicant who sends a pre-interview love notes to one program sends a similar note to all of the others, too. (This suspicion is informed by my own observation that these notes frequently mention other programs or hospitals by name, due seemingly to a faulty find-and-replace function.)

The advantage of sending an official signal is that it’s credible. An otolaryngology program that receives one knows that there are at most 4 other programs who got the same signal from that applicant. So if you don’t send a signal, don’t waste your time sending an e-mail. (Honestly, if formal preference signaling does nothing more than eliminate insincere pre-interview love notes, it would still be a victory.)

–

LOSER: The honor system.

As suggested above, the honor system just doesn’t work for pre-interview communication between applicants and programs. Formal preference signaling does because a trustworthy intermediary transmits the signals and vouches for their authenticity.

For otolaryngology/head & neck surgery (OTO-HNS) applicants and programs, that intermediary will be the OPDO (with the broad support of the Society of University Otolaryngologists (SUO) and Association of Academic Departments of Otolaryngology (AADO)).

To allow applicants to feel safe in submitting their signals, the OPDO’s plan imposes some simple rules:

- Programs will not divulge the identity of applicants whose signals they receive.

- Programs will not be permitted to ask interviewees where they signaled.

- Programs will not publicize the number of signals they’ve received.

It would be easy for any specialty who wants to implement preference signaling to copy the otolaryngology plan. Alternatively, any specialty who wants preference signaling but is concerned about managing the logistics within their program directors’ organization can easily outsource that intermediary role to a third-party online platform like Signal.

–

WINNER: West Coast applicants to East Coast programs.

As applicants apply to more programs, it becomes more difficult for program directors to distinguish those with sincere interest in their program from those who are applying indiscriminately. To avoid going unfilled in the Match, the program must make a decision.

Option #1 is to interview more people. Often this is the best choice. Interviewing applicants is good advertising for your hospital, and may pay dividends down the line with faculty recruitment or favorable word-of-mouth. But it’s also expensive and time-consuming.

Option #2 is to interview applicants that seem to have a higher probability of matching at the program. One key factor there is geography: experience shows that most matches come from schools that are geographically close to the program. (In anesthesiology, for instance, an applicant from the same state as the program enjoys a benefit equivalent to 4.1 points on USMLE Step 1 in terms of being offered an interview.)

Obviously geography is an imperfect surrogate for sincere interest. For every handful of applicants who apply to a far-flung program on a lark, there’s someone else whose significant other or childhood home is in that city. Now, those applicants have a way of demonstrating their sincerity.

–

LOSER: Applicants with 6 favorite programs.

Because they only have five signals.

Whatever n number of signals are allowed, there will always be someone who has serious interest in n+1 programs. And there will also be someone who is only really interested in n-1 programs, but they’ll send out n signals because hey, why not?

Determining how many signals to allow takes some judgment. Allow too few, and you may ignore applicants who sincerely want to get your attention. But allow too many, and presence of a signal doesn’t tell a program much. In this case, the lack of a signal may be more informative – and be used as a hard screening mechanism.

(Time will tell, but to me, 2-5 signals seems about right.)

–

WINNER: OTO-HNS program interview budgets.

Interviewing has always been the most expensive step in the Match process for applicants. In 2016, the average OTO-HNS applicant spent $5400 on applications and interviews, with the bulk of that figure being spent on the latter.

This year, virtual interviews will reduce the financial and opportunity costs of interviewing for applicants – and it’s likely they’ll complete more interviews if given the chance to do so.

But even virtual interviews are still expensive for programs.

One ophthalmology program estimated the cost of interviewing at $3,736 per applicant – mainly due to lost clinical productivity for faculty. Figures for otolaryngology programs are likely similar, insofar as any faculty member who spends a day interviewing applicants might instead have been in the OR, engaged in the gainful practice of head and neck surgery.

–

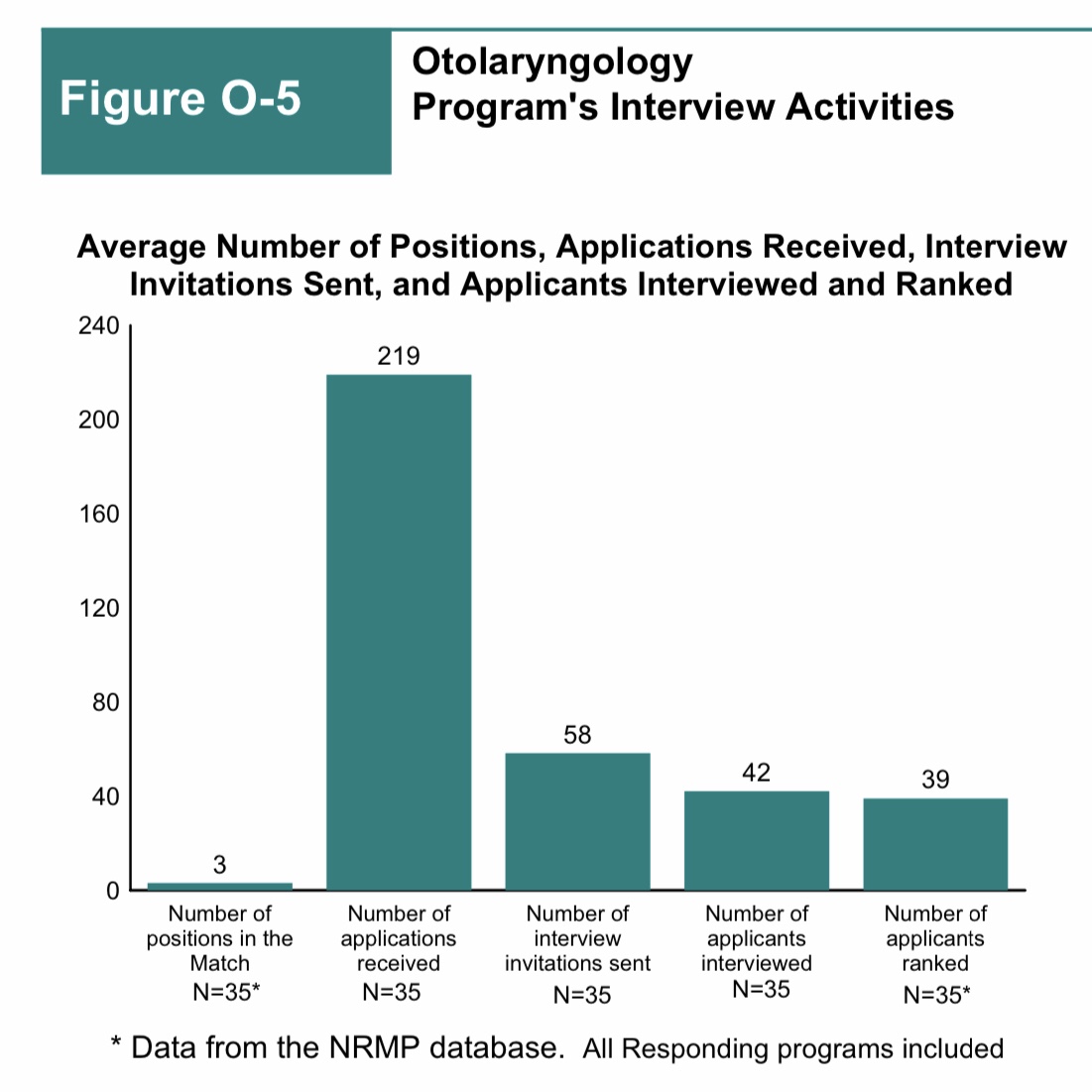

According to the NRMP’s Program Director Survey, the average otolaryngology program issues 58 interview invitations.

LOSER: “Top tier” programs.

As great as preference signaling sounds, there are some problems.

Say you’re an applicant with one signal left to send. To which program should you send it?

A. A prestigious “reach” program, where you may not be offered an interview;

B. A lesser-known program that you sincerely like – but where your credentials are probably good enough to be offered an interview without sending a signal

Otolaryngology applicants are a bright bunch, and most of them will realize that the correct answer is A.

To maximize the number of interview offers you receive, you should send your signals to programs where you might not be offered an interview without them. Unfortunately, the more that applicants apply this strategy, the more unintended consequences we’ll see.

In a worst-case scenario, “top tier” programs will receive so many signals that they begin to use them as a hard screening mechanism. Does that seem farfetched? I don’t think so.

Suppose that a “top tier” OTO-HNS program receives signals from 100 applicants – a plausible figure given that there were around 500 applicants to otolaryngology programs last year.

But as shown above, the average otolaryngology program invites only 58 applicants to interview.

If you’re the PD, and you already have 100 applicants signaling their interest, why even look at the other couple of hundred applications you received? Why chase birds in the bush when there are so many in your hand? Why play from behind and try to convince an applicant to come to your program when you know you’re at best 6th on their list?

But as soon as applicants perceive that the “top tier” programs are using the lack of a signal as an exclusionary criterion, then every applicant will submit a signal to these programs in order to ensure their application gets even cursorily reviewed. And when every application to a particular program is accompanied by a signal, it defeats the purpose of signaling altogether.

In a best-case scenario, the selectivity of otolaryngology saves the day. Remember, only 348 of the 504 applicants to otolaryngology (69%) matched last year – so an applicant who spends all of her signals to the Top 5 programs in the Doximity reputation rankings misses an opportunity to highlight her application to PDs at other programs where her chance of matching is probably higher.

In either scenario, it should be apparent that, the fewer signals a program receives, the more valuable each one becomes – so prestigious programs are likely to derive less benefit from preference signaling than others.

–

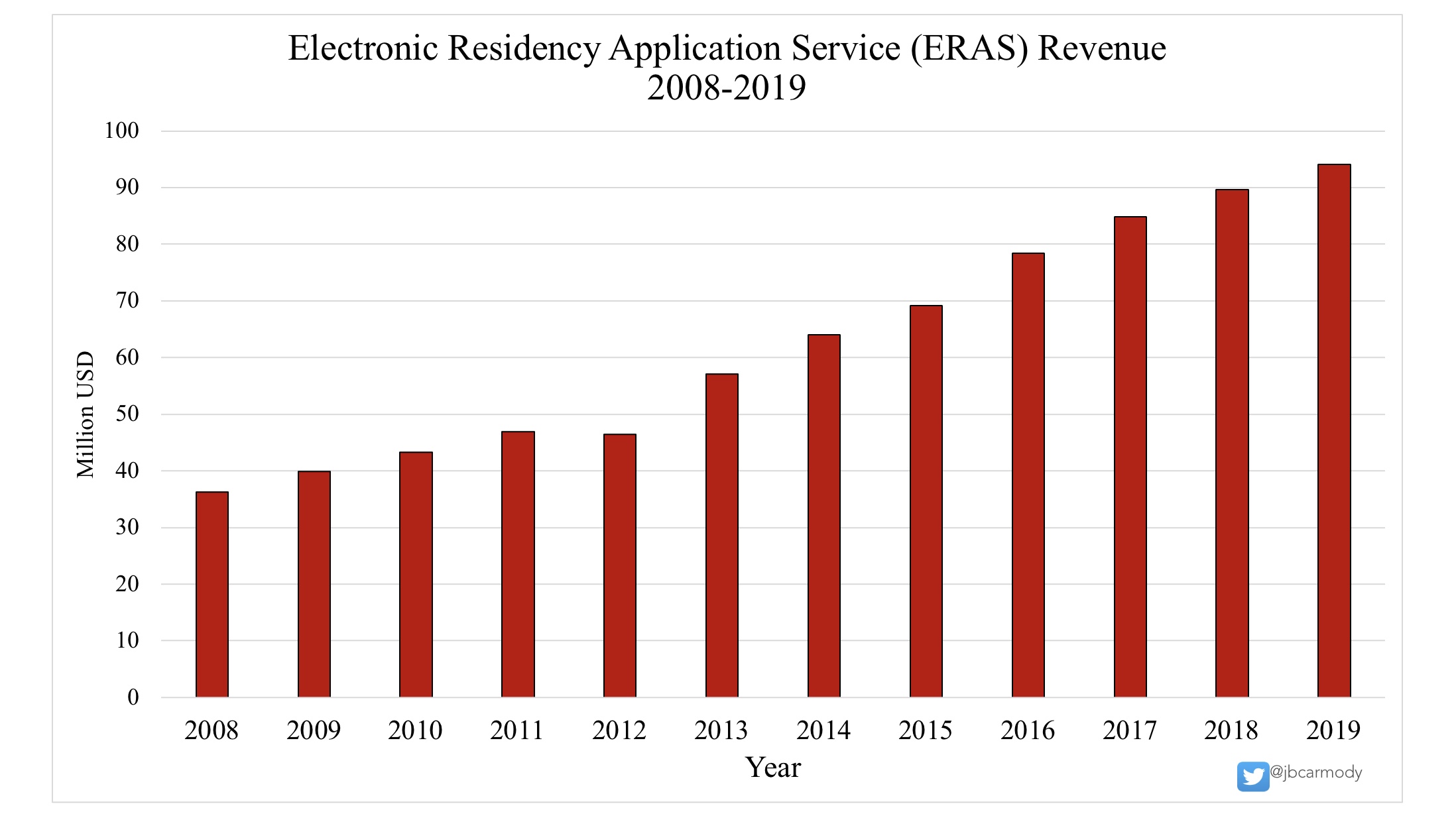

WINNER: ERAS revenue.

There’s one other problem with preference signaling: the ability to designate certain applications as being special means that applications that are not special become systematically devalued. And if regular applications aren’t as valuable, then a rational applicant will submit even more of them to stack the odds in their favor.

There’s only one group who wins – and it ain’t program directors, and it ain’t applicants. But the Association of American Medical Colleges – sponsor of ERAS – will keep laughing all the way to the bank.

With Application Fever, the Association of American Medical Colleges is the big winner.

–

LOSER: Continuous variables.

Under the OTO-HNS plan, signals are binary. A program either receives one, or not.

Using a binary variable limits the amount of information that a signal can contain. A program who receives a signal knows that their program is somewhere in the applicant’s top five programs pre-interview – but the difference between #1 and #5 may be huge.

But what if the signal were a continuous variable?

Suppose that applicants were allocated 100 points to distribute among all the programs to which they applied. This would better allow applicants to demonstrate their degree of preference.

Consider, for instance, an applicant whose significant other lives in a city with one otolaryngology program. She sends a signal to her dream program – but the signal they receive is indistinguishable from the one that four other programs will receive, even though she has much less interest in those programs.

On the other hand, if signaling were a continuous function, she might reasonably allocate 60 points to her dream program and the remaining 40 across all the other programs to which she applied.

A continuous variable could also be used as a sortable metric, which could be nice. But that’s still not the most important benefit of continuous variable preference signaling.

Binary preference signaling does nothing to address Application Fever. If anything, it provides an incentive for applicants to apply to even more programs, as suggested above.

But imagine how things would different if the signal were a continuous variable, and if the applicant had to assign some numeric value to each application submitted.

Now, each additional application becomes incrementally less valuable – and applicants have a disincentive to apply excessively, since the more programs to which you apply, the fewer points you can allocate to each.

With a binary signal, an applicant can apply to another ten or twenty programs, “just in case” – and each of those applications looks identical to one received by their 6th favorite program. With a continuous signal, an applicant would have to be honest about his low level of interest in those programs by assigning them an interest signal that might be just a fraction of a point.

–

WINNER: Newton’s First Law of Motion.

There is an incredible inertia that applies to academic medicine. Left at rest, the system stays at rest. All the problems in the current system will remain problems in the future – unless we put in the effort to fix them now.

Preference signaling is no panacea – but I think it will make things better for OTO-HNS applicants and programs this season. Better still, if certain aspects of the system need to be tweaked in future cycles, the OTO-HNS program directors will have the data to inform sensible decisions.

To me, the fact that otolaryngology program directors were able to generate sufficient force to overcome the natural inertia of our current systems is a major success – and hopefully one that inspires others to do the same.

–

ADDENDUM: In October 2020, I spoke at the NRMP’s Transition to Residency meeting in a session on preference signaling. My job was to argue the “Con” position in a pro and con debate. If you’re interested, you can watch my portion here. (And if you’re wondering, yes, I won the debate by convincing more audience members of my position during the session.)

Since then, I’ve had a few people ask me what I really think about preference signaling, because the article here is generally positive, but I took the opposite position during the debate. (And yes, I stand by everything I wrote (and said)).

Whether preference signaling is the solution depends on how we define the problem. If your goal is to reduce overapplication, preference signaling ain’t gonna fix it. On the other hand, if your goal is to improve the quality of matching by ensuring that interested programs and applicants can find each other in an increasingly chaotic marketplace, then I think preference signaling holds promise.

Ultimately, I think there’s equipoise on this issue – and that’s why it’s worth pursuing. Whether you think preference signaling is good or bad, until we collect data, we’re all just speculating. That’s why I have great respect for the otolaryngology program directors for taking the first step (and wish more people in medical education had the courage to answer questions empirically instead of stubbornly defending the status quo with hot-headed rhetoric).

–

YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY:

Virtual Interviews: Winners and Losers Edition

The Residency Selection Arms Race, Part 1: On Genghis Khan, Racing Trophies, and USMLE Score Creep

On Toilet Paper and Application Caps